Harvey Dunn (1884-1952) is one of South Dakota's most famous and noted artists. He is beloved by many in the state for the power and spirit of his prairie pioneer paintings. The imagery he created as a war artist in WWI is some of the most compelling and popular because of its honesty and starkness.

But Dunn's biggest claim to fame, the one that spread his images across America and served as the foundation of his practice, is his work as one of America's foremost illustrators during the Golden Age of Illustration.

Born on a South Dakota homestead in 1884, Dunn showed talent for drawing early on. He would sketch with his mother in the evenings by kerosene light and littered the chalkboard of his one-room schoolhouse with so many drawings that his teacher had to hide the chalk to conserve it. As a teenager he sent a letter to illustrator Charles Dana Gibson asking him how he could follow in his footsteps. At age seventeen Dunn entered into preparatory courses at South Dakota State University (then known as Dakota Agricultural College) with the intent of studying art. Here he met art professor Ada B. Caldwell, who Dunn says showed a "serious, loving and intelligent interest in what I was vaguely searching for." Caldwell advised Dunn to pursue further art training at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. While studying there from 1902-1904 he met the "Father of American Illustration," Howard Pyle, who invited him to apply to his prestigious school of illustration in Wilmington, Delaware.

Pyle's studio school had just been formed in 1900 and would become known in time as the "Brandywine School." Pyle had established it in the hopes of fostering excellence in American illustration by focusing on a small number of students who showed especially strong promise. Of the hundreds of students applying annually only a handful were chosen. Dunn was in elite company when he was selected.

Pyle began teaching illustration out of necessity. With no formal school for illustration in existence in America at the time, Pyle's education was a combination of formal training in fine arts and hard-gained, self-taught lessons from years of experience in the publishing industry. The explosive growth of the American publishing industry at the end of the 20th century had created unprecedented opportunities for artists, and their images were beginning to hold incredible sway over the minds, tastes and consumptive habits of the reading public. Pyle was acutely aware of the power that illustration held in shaping American identity, its role as an art-form for the people and its special importance in captivating the audience's attention. His sense of responsibility for this fueled a criticality that evolved American illustration as an art-form, taking it from staged depictions to dramatic and gripping expressions that enveloped readers in their stories.

Many artists trained as painters had difficulty adjusting their work to the needs of printing and publishing and many were mere copyists lacking imagination. So it was with the encouragement of editors, who were equally frustrated by the state of the field, that Pyle first began teaching illustration in 1894. He was both a tough disciplinarian and an inspiring teacher "who brought out the best in each student's abilities." Pyle taught necessary skills in picture-making for the publishing industry but more importantly he taught to not merely depict or replicate when illustrating but to create impact and capture emotional significance. He taught students to enter into their pictures, to experience the same feelings that the characters were experiencing, in order to express them more faithfully.

"Project your mind into your subject until you actually live in it. Throw your heart into the picture and then jump in after it ... Art is not a transcript of nature nor a copy ... Art is the expression of those beauties and emotions that stir the human soul ... "

Pyle and his students played a defining role in establishing American illustration as the envy of its European counterparts. Dunn prescribed to Pyle's methods and philosophy of illustration whole-heartedly and with near-religious devotion, studying with the master from 1904 to 1906.

After opening a studio near his teacher's in Wilmington, commercial advertising work and assignments from popular magazines like Scribner's, Harper's, Collier's Weekly, Century and Outing started coming in for Dunn. Two illustrations in this show were from Dunn's first book illustration assignment in 1906 for Dead Men Tell No Tales. Dunn was prolific, punctual and dedicated, and had no trouble finding work. At one point he was able to complete 55 illustrations for various clients in just 11 weeks. The Saturday Evening Post became a leading showcase for his talents, with Dunn creating over 250 illustrations for that single magazine alone.

Dunn tended to downplay his achievements and credited his success in illustration largely to timing. It is true that his entry into the field was perfectly aligned with the peak of America's "Golden Age" of illustration, just after the turn of the 20th century. It is also true that he was educated alongside the best students by the best teacher, a truly innovative ground breaker in the field. But Dunn also had incredible natural talent and shared with his teacher the ability to be both grounded and imaginative, with a serious sense of purpose and high ideals. He drew upon both strength and tenderness in seeking out balance and vitality in his works. His work ethic, vigor and tenacity were notorious, and would have served his success in any endeavor.

Dunn turned to teaching shortly after Pyle passed away in 1911. In speaking of his own teaching, he claimed "All that I am really doing is carrying on the Howard Pyle idea." As Dunn put it in a lecture to his student, Dean Cornwell, "When doing an illustration, the first step is to feel your subject, then the idea and last the composition." What mattered wasn't polished techniques but grappling with powerful feelings and ideas-finding and expressing in a compelling way the driving motivation behind a universally human image.

Howard Pyle had taught Dunn to make paintings that speak for themselves, stating that it's "utterly impossible for you to go to all the newsstands and explain your pictures." When a woman once asked what the title of a painting was, Dunn notoriously quipped, "Madam, if you need a title to know what that picture is all about, I have failed!" It is safe to say that Dunn intended his paintings to stand on their own as they do, without any titles or accompanying stories. Reading the stories that Dunn brought to life in his paintings does not need to diminish or supplant the imaginings of those who have only viewed the paintings thus-far though. These stories are just more chapters in the larger story of Harvey Dunn, and sharing them is a means of fostering a greater understanding of the man, his works and the era of American storytelling that he was such an integral part of.

Excerpts from Stories Dunn Illustrated

Dunn's untitled painting often called "Red Cross" was the story illustration for The Three Things: The Forge in Which the Soul of a Man was Tested by Mary Raymond Shipman Andrews, Ladies’ Home Journal, December, 1915.

Author Mary Raymond Shipman Andrews (1860-1936) was the daughter of a Kentucky Episcopalian rector. Popular magazines of the era, such as Scribner’s and Ladies’ Home Journal regularly published Andrews’ historical fiction, short stories and poetry.

The Three Things: The Forge in Which the Soul of a Man was Tested recounts the war experiences of Philip Landicutt, an heir to a British steel fortune. Apparently the author based the story on the Battle of the Yser, which took place in October 1914. Shrapnel injuries received in Belgium inspired Philip to promise his life’s work to God. Philip is first tested when he wakes up on a hospital cot, with enemies on either side of him. On one side is a kindly, middle-aged Prussian man; the other is a 17-year-old German boy who dreams of returning to his mother and sister. Philip befriends his enemies and returns to his family in England. Before he was injured, Philip promised an orphaned Belgian girl his help. This girl greets Philip upon his return home. The story concludes with Philip, his family and the Belgian girl agreeing to devote their lives to social work.

See this illustration as it was presented in the Ladies’ Home Journal

The entire book text is available on the Hathi Trust Digital Library

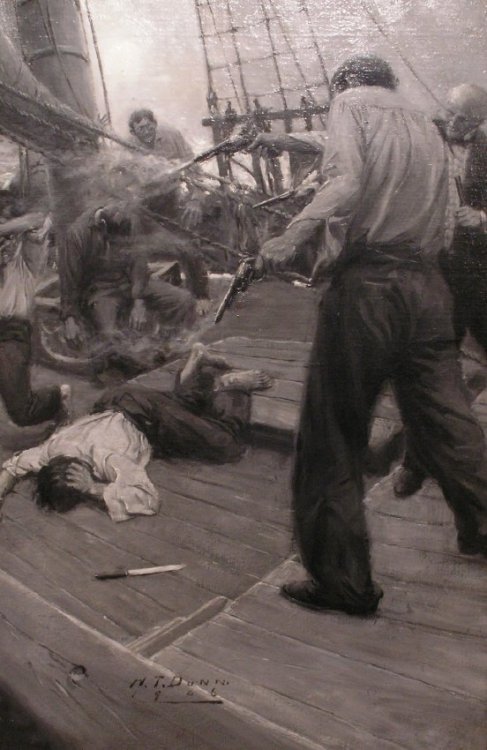

He and Harris Shot Every Man of Them Dead

"The same thing came into play aboard the schooner. Never shall I forget the horror of that voyage after Santos came aboard! I had a crew of eight hands all told, and two he brought with him in the gig. Of course they began talking about the gold; they would have their share or split when they got ashore; and there was mutiny in the air, with the steward and the quarter-master of the Lady Jermyn for ring-leaders. Santos nipped it in the bud with a vengeance! He and Harris shot every man of them dead, and two who were shot through the heart they washed and dressed and set adrift to rot in the gig with false papers."

From "Dead Men Tell No Tales" by E.W. Hornung, 1907.

The entire book text is available at the Library of Congress.

Learn more about Harvey Dunn through this video, produced for the traveling exhibit Masters of the Golden Age: Harvey Dunn and His Students (2015-2016). Thanks again to the exhibit sponsor, First Bank and Trust.

This recording of South Dakota Art Museum Guild Vice President and retired South Dakota Art Museum Exhibitions Curator, John Rychtarik, presents a fascinating talk John gave for the South Dakota Historical Society based on his experience with Harvey Dunn paintings before, during and after his time as the Exhibitions Curator at the South Dakota Art Museum. His talk includes discoveries made during conservation work…thus the title, What Lies Beneath? It was updated and presented to the Art Guild on April 27, 2021.